As our software development processes have evolved we’ve mostly said goodbye to the idea of defined product versions. Many modern product delivery teams are taking this a step further — even the concept of a “product release” is starting to fade. Instead our products are becoming a fluid, rapidly evolving set of features, assembled uniquely for any given user.

There’s great opportunity here, but risk as well. We must learn how to succeed in a post-release world. But first, we need to understand how far we’ve come.

Death of the Version

25 years ago a new release of a software product was a notable event. The marketing department would even insist on a catchy version name for the release. Internet Explorer 6, Office 2000, Windows XP, OSX Mountain Lion. This is still the case for a few types of software — operating systems being the most notable — but for most of the software products we use on a daily basis the concept of a version has faded away. What version of Google Maps are you using these days? How about Facebook? Twitter? As far as the end-user is concerned there is no version, just “current.”

As far as the end-user is concerned there is no version, just “current.”

What killed the version?

A few different forces have moved software products away from release versions. The rise of agile software methodologies and associated practices such as Continuous Delivery has allowed software teams to tighten up software delivery cycles dramatically. Products that were once released every few months are now released every few days.

In parallel, the growing capabilities of the web as a platform has moved many products off of the desktop and into the browser. This has greatly reduced the friction involved in releasing a new version of a product. Pushing a code change to servers you manage is a lot easier than persuading your users to download and install an update.

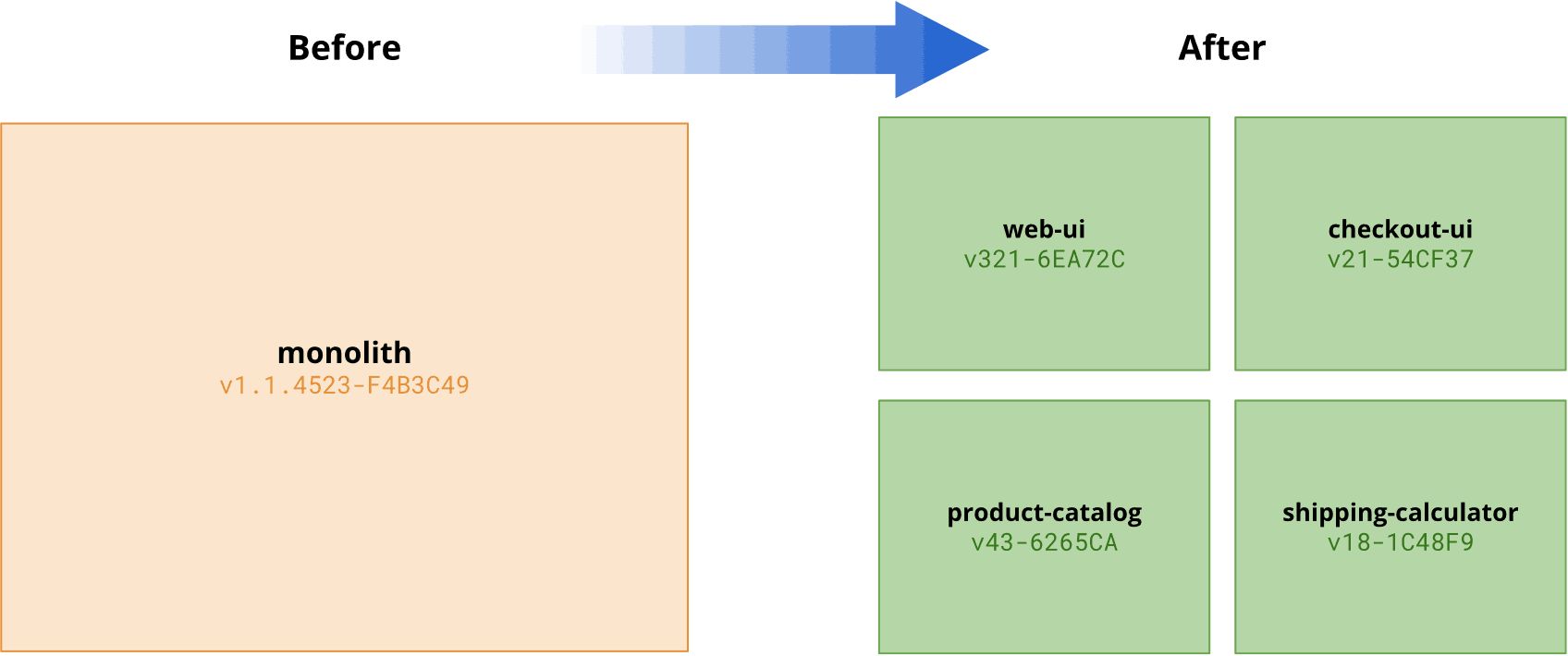

Finally, there has been an architectural shift away from large monolithic systems towards service-oriented architecture, and in recent years microservices. These modern architectures consist of many small, independently-deployable units. This again reduces the friction around deploying a code change by reducing the scope of the deployment to one specific service.

These forces combined have led to software release cycles shortening dramatically — from multiple months or years between each release to a rate of weekly, then daily, then hourly software delivery for some teams. Delivery of a new software release has moved from a marketing event with fanfare to something that is happening almost continuously, even for really large products — engineers at Amazon were releasing changes to production every 11.6 seconds, back in 2011!

Death of the Release

The marketing of product versions to consumers has declined, but product delivery teams still assign a unique version to each release of a deployable artifact. This internal release identifier is used to manage deployments, and to correlate changes in an environment — i.e. a bug or a performance degradation — with a software change.

However, the utility of these internal release identifiers has also been shifting in the last few years. It used to be quite typical to ask “which release were we running in our staging environment when I observed that bug?”, or “which release are we deploying to production?”. These concepts are no longer applicable for modern delivery teams.

As teams move from a monolith to microservices there is no longer one deployable unit, but rather an ecosystem of independently deployable services. It no longer makes sense to ask which version of a release is running in an environment. Instead we must ask which version is running for each individual service.

Even the assumption that an environment has one specific release of a given service is becoming shaky. Continuous Delivery practices such as canary releasing and blue/green deployments mean that there may well be multiple different releases of a service running simultaneously in an environment.

And then there’s feature flagging. One can think of a feature-flagged service as existing in a sort of quantum superposition of potential code paths, resolving to a specific set separately for each request. This means that a service’s behavior in an environment can change radically without any code deployment and without any observable change to the release version.

As we move from Continuous Delivery to Continuous Experimentation we are reaching the point where it is no longer useful to attempt to describe the current running software in terms of a “release”, or even a set of releases. The situation has become a lot more fluid.

One can think of a feature-flagged service as existing in a sort of quantum superposition of potential code paths, resolving to a specific set separately for each request.

Building products in a post-release world

How should we cope with this new, post-release world? It is clear that modern approaches like microservices and continuous experimentation are a boon to product delivery teams. They allow us to move faster with more safety, thanks for the tight feedback loops they enable.

But, this new world also brings challenges.

What codepaths were involved?

It can be a lot harder to diagnose a bug when you’re not sure what code was involved! The load on testers becomes greater as they need to consider the interaction between multiple releases of different services — each with different feature flags which can behave differently from request to request.

Stop moving my cheese!

From a user’s perspective, a product’s rapid pace of change can be a little overwhelming. New features arriving frequently is nice, but having the UI change every time you log in can be disorienting. Even worse is when a feature is available one day and then gone the next. Users can also be wary of the idea that they’re not getting the same experience as other people, particularly if there is any whiff of unfair business practices.

Interfering experiments

Ironically while this accelerated feature delivery is partly enabled by Continuous Experimentation practices, that same speed of change can itself actually interfere with feature experiments. It can be hard to statistically correlate an uptick in a KPI with a feature experiment when there are other changes happening over the course of the experiment.

Observability is king

Enhancing the observability of your software — the quality of logging and other instrumentation — is one key way to mitigate some of these challenges. Structured logs should include contextual metadata with every log such as:

- The current build identifier

- An environment identifier (i.e. staging vs production)

- A request identifier, or preferably distributed trace identifiers

- Feature flag state for the current request (which flags are on for this user, right now)

This metadata can be invaluable in providing additional context when diagnosing a bug or other production issue.

Including similar metadata in analytics events also makes it a lot simpler to correlate behavior back to the set of features which were in play, and can help in identifying and correcting for bias introduced into an experiment by an unrelated feature change.

Fewer flags, greater throughput

Keeping the number of active feature flags reasonably low can help on a variety of fronts. It reduces the testing burden of multiple interacting flags, as well as the risk of experiments interfering with one another. Fewer active flags also mean fewer things changing at once for your users.

Broadly, it’s more beneficial to focus on “flag throughput” — the rate at which flags move from being introduced to being retired — rather than volume.

Centralized management

Managing all feature flags in a shared system can help in understanding the number of active flags and avoiding interfering experiments. Centralized flag management also means you can batch up a set of feature changes into a single release, which helps avoid overwhelming your users with many small changes. A centralized system makes it easier for testers to see which flags they should expect to be in play within different systems, and how those flags might interact.

A new era

We’re entering an era which will involve a massive explosion in the rate at which we release new experiences to our users. Embracing this next stage in the evolution of product delivery can enable teams to move faster, and with greater safety. But entering this brave new world requires us to develop new practices if we’re to avoid the pitfalls of a post-release world.

Get Split Certified

Split Arcade includes product explainer videos, clickable product tutorials, manipulatable code examples, and interactive challenges.

Switch It On With Split

The Split Feature Data Platform™ gives you the confidence to move fast without breaking things. Set up feature flags and safely deploy to production, controlling who sees which features and when. Connect every flag to contextual data, so you can know if your features are making things better or worse and act without hesitation. Effortlessly conduct feature experiments like A/B tests without slowing down. Whether you’re looking to increase your releases, to decrease your MTTR, or to ignite your dev team without burning them out–Split is both a feature management platform and partnership to revolutionize the way the work gets done. Switch on a free account today, schedule a demo, or contact us for further questions.